Monday of the Twenty-seventh Week in Ordinary Time, October 6, 2025

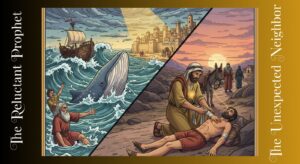

The Reluctant Prophet and the Unexpected Neighbor

Jonah 1:1—2:1.11, Psalm: Jon 2, Lk 10:25-37

My dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ,

The Word of God today presents us with two of the most compelling figures in all of Scripture: a runaway prophet and a compassionate outsider. At first glance, the story of Jonah and the parable of the Good Samaritan seem unrelated. Yet, the Holy Spirit weaves them together to teach us a profound lesson about the expansive, unsettling, and merciful heart of God—a heart we are called to make our own.

Jonah is a prophet, but a deeply reluctant one. When God calls him to go to Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian empire, and preach repentance, he flees in the opposite direction. Why? Because Nineveh was the enemy. The Assyrians were brutal oppressors of Israel. Jonah doesn’t want them to be saved; he wants them to be punished. He would rather face a storm and be thrown into the sea than participate in God’s merciful plan for his enemies. Jonah’s problem is not a lack of faith in God’s power, but a resistance to the breadth of God’s mercy.

In the Gospel, a scholar of the law asks Jesus the fundamental question: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” He correctly answers: love God and love your neighbor. But seeking to justify his own limited circle of care, he asks, “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus responds with the parable of the Good Samaritan. A man is beaten, robbed, and left for dead. A priest and a Levite—religious figures who represent the established order—see him and pass by. But a Samaritan, a member of a group despised by the Jews, is moved with compassion. He crosses every cultural and religious boundary, tending to the man’s wounds, bringing him to an inn, and paying for his care.

Here lies the connection. The scholar of the law, like Jonah, wanted to define the boundaries of “neighbor.” He wanted a manageable list of who was worthy of his love. The priest and the Levite saw the wounded man not as a neighbor, but as a complication, a threat to their ritual purity. The Samaritan, however, embodies God’s own definition of neighbor: anyone in need, especially the enemy, the outsider, the different one. The Samaritan is what Jonah was called to be: a bearer of unexpected mercy to those deemed undeserving.

For us, the challenge is clear. We all have our own Nineveh, our own road to Jericho. We have individuals or groups we secretly believe are beyond the pale of God’s mercy—or ours. We can be tempted to flee from the call to love them, or to pass by on the other side of the road, justifying our indifference.

Pope Francis constantly calls us to be a “Church that goes forth,” a field hospital that tends to the wounded on the margins. He reminds us, “Mercy is the Lord’s most powerful message.” This mercy is not a theory; it is a verb. It is the Samaritan stopping, bending down, and pouring oil and wine. It is the willingness to be inconvenienced for the sake of love.

St. Mother Teresa put it bluntly: “If you judge people, you have no time to love them.” The parable of the Good Samaritan and the story of Jonah call us to replace judgment with compassion. They ask us: Who is the person you struggle to love? Who is the “Ninevite” in your life? Who is the wounded stranger on your daily path?

The comfort today is that God’s mercy is greater than our reluctance. He pursued Jonah even into the storm and the belly of the fish, giving him a second chance. He gives us the same grace. He does not demand that we feel affection for our enemies, but that we act with compassion. He asks us to stir into flame the gift of the Holy Spirit we received in Baptism, the Spirit who is the very love of God poured into our hearts.

Let us pray for the courage to stop running. Let us ask for the grace to see with the eyes of the Good Samaritan, so that we may truly become neighbors to all, and in doing so, inherit the eternal life that is promised. Amen.